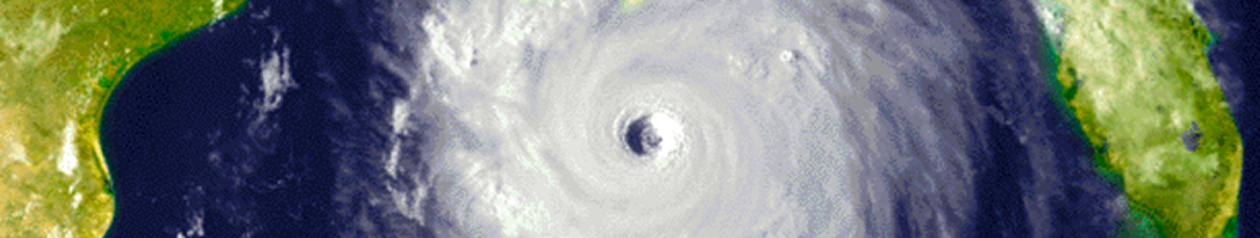

The barrier islands of the Gulf Coast are an important defense against hurricanes. Mostly uninhabited, they are the first landforms that a Gulf Coast hurricane strikes. While they do not weaken the hurricanes (they aren’t large enough), the islands take the brunt of the hurricane’s storm surge, diffusing it somewhat before the eye makes landfall on the mainland. They are also an important defense against tsunami, a real (if little-known) threat. Significant seismic activity has occurred in the Gulf of Mexico fairly recently.

Global warming is predicted to melt part of Greenland and/or West Antarctica, raising sea levels worldwide up to 20 feet (more if all of Greenland and some of West Antarctica melted). This would have horrific consequences on coastal cities around the globe, of course. This blog, however, will focus on one specific area — the United States Gulf Coast. (Ha, doesn’t it always?)

If global warming raised sea levels as predicted, most of low-lying Louisiana — as well as the critical barrier islands — would be underwater. The low-lying swampland of Louisiana, which has been receding for years now, is another natural barrier for the coast, as well as an environmental treasure. It too would be covered in water.

The coastline would lose its natural defenses against hurricanes.

And, as research is indicating, global warming would also intensify the hurricanes themselves.

The EPA produced a series of pictures showing the coastal areas that are most at risk from global warming-induced inundation. Red indicates areas that are less than 1.5 meters above sea level. The images can be clicked on to show a larger view.

Here is an image of Louisiana and Texas:

And here’s one of Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida:

It’s hard to see on these maps, but the barrier islands are the thin trail of red south of the main coastline. They would be underwater.

More disturbingly, from the National Environmental Trust, here is a QuickTime movie of how Biloxi, MS (and its barrier island) would be affected by a rise in sea level. (WARNING for dial-up users: 3 MB file!) I’ve linked to the movie from this graphic I’ve made showing how the coastline would be inundated.

The barrier island protecting the city would no longer exist. Sure, the projection of the land would still exist underwater, and would serve to slightly lessen the impact of a storm surge, but it isn’t at all the same as having a true island above the sea. A dry, projecting landmass stops the flow of water, at least temporarily, and breaks the waves. A former island that has gone underwater obviously doesn’t keep the water from flowing.

Also, as you can clearly see, the city itself would be partially underwater. This includes the glitzy new development that is taking place on this part of the coast in response to Hurricane Katrina — very shortsightedly, I ought to add. Whether this is because of the government of Haley Barbour, who is very likely a global warming skeptic, or because the businesses are aware of the risk but decided to hedge their bets, I do not know.

The Katrina recovery and rebuilding process is not taking global warming into account at all. When the next really bad hurricane strikes, its impact could be compounded by the effects of global warming. The coast will be farther inland due to rising waters, there will be fewer natural barriers, and the hurricane itself is likely to be stronger and wetter than it would be without global warming. And, as unfortunate as it is for me to say this, at this point it’s not enough to simply drive less, replace incandescent light bulbs with fluorescent, cross our fingers, and hope that we’ve stopped the problem.

I absolutely support cutting carbon emissions. If we don’t, the consequences will be even more horrendous than the scientists are daring to predict right now. But we’ve reached a point where it would be nothing short of grossly irresponsible to fail to look into preparation for the potentially disastrous changes that we have brought upon ourselves.